McCullough’s Best of 2025

Each year, the McCullough team reflects on the projects that defined our work, those that challenged us, inspired collaboration, and reinforced the power of thoughtful landscape architecture. In 2025, our designers partnered closely with clients and project teams to shape places that respond to their context, serve their communities, and stand the test of time.

From commercial and educational campuses to hospitality, housing, institutional, and mixed-use environments, this year’s selected projects span San Diego, Los Angeles, and Northern California. In the stories that follow, each designer shares why they chose their project and the design moments that made it a standout—our collective Best of 2025.

Rocky Young Park at Pierce College

RockY Young Park at Pierce College

David McCullough, PLA, ASLA

Principal Landscape Architect

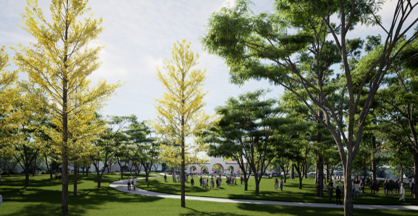

In 2024, McCullough partnered with HPI Architecture to reimagine Rocky Young Park, an aging site at the heart of Los Angeles Pierce College. Following a successful pursuit, design commenced in 2025 with a vision to transform the underutilized space into a vibrant "Central Quad" and social hub.

The design team, led by Los Angeles-based McCullough Associate, Kira Becker was tasked with creating a flexible, "naturalized" park capable of evolving with the campus’s needs, both seasonally and over decades. McCullough’s conceptual response centers on a sweeping meadow: a large, open greensward framed by a lush tree canopy. At its heart lies a central stage area designed for large-scale events like commencement, while the sheltered perimeter offers intimate, "pocket" social spaces tailored for diverse student groups.

The park acts as a critical connective tissue for the campus:

East: It anchors the Library, Cafeteria, and "Free Speech Mall."

West: It creates a natural buffer for the Center for Sciences and Vet Tech facility.

North: It redefines the campus’s public face with a new Northern Gateway. This arrival experience includes a welcome plaza and a gateway arcade, creating a formal "front door" from the campus’s largest parking area.

Once completed, Rocky Young Park will transition from a pass-through space into a true destination, a place of assembly, identity, and respite for students and faculty alike.

Kira Becker and I, at McCullough, lead the design inspiration for this project through schematic design and are looking forward to watching the execution of the park.

For these reasons, I have selected Rocky Young Park as my Best of 2025.

Historical Context: Rocky Young & Pierce College

Who was Rocky Young?

Dr. Rocky Young served as the President of Pierce College from 1999 to 2004 and later as the Chancellor of the Los Angeles Community College District (LACCD). He is widely credited with "saving" Pierce College during a period of declining enrollment and budget crises.

The Visionary: Young spearheaded the Pierce College Master Plan, which shifted the campus from a collection of bungalows into a modern, cohesive academic environment.

The Connection: Naming the park after him was a tribute to his belief that a campus should feel like a community. His philosophy was that students succeed when they feel a sense of "place."

The Significance of the Site

Agricultural Roots: Pierce College (founded in 1947) is famous for its agricultural history in the San Fernando Valley. The "naturalized" approach McCullough is taking honors this heritage by bringing back native-leaning landscapes rather than purely urban hardscape.

The "Hub" Concept: Historically, the Pierce campus was spread out due to its origins as an ag-school. This project is significant because it finally creates the centralized urban core that the campus has lacked for 70 years.

Axis at Millenia is a premier example of how "Smart Growth" and thoughtful landscape integration can lead the development of a vibrant, pedestrian-centric, urban development. Axis is one of many developments within the larger Millenia master planned community in the City of Chula Vista, CA.

Millenia is a 210-acre, master-planned "urban village" that serves as an intentional departure from traditional Southern California sprawl. Designed to mirror the density and walkability of downtown San Diego, and other successful urban developments, the neighborhood is comprised of an intended 80 walkable city blocks. Its primary goal is to support a high-energy, mixed-use environment where residents can live, work, and play without total reliance on vehicles. By intertwining high-density residential projects with civic spaces, retail, and a robust transit hub, Millenia creates a sustainable urban ecosystem that prioritizes human connection and outdoor activity.

The design team was composed of the talented architectural designers at KTGY, the competent engineering group at Hunsaker & Associates, and the visionary development team at CalWest lead by the experienced and discerning Jeb Hall. The cross-disciplinary communication and iterative process resulted in a project that was both unique and reflective of the overall community aesthetic the overall Millenia development sought to express.

Modern Meets Organic

Axis at Millenia exemplifies the "modern-meets-organic" design language that defines the district. The project is strategically designed to blur the lines between private living and public recreation, offering a seamless transition from its industrial-modern townhomes to the surrounding greenbelt and park space.

Instead of being centered around a grand plaza or central monument, Axis features a series of dispersed color gardens at the terminus of each housing cluster. These garden spaces showcase a particular floral color, along with seating and a small place to gather. These plazas serve to bring character and diversity to the project as a reflection of the values Millenia seeks to express.

In addition, a sophisticated outdoor community pavilion allows for larger gathering toward the south-west of the project. This space features high-end barbecue grills, outdoor dining areas, and a community pergola designed for social gatherings. The lighting design uses DarkSky approved fixtures and catenary lighting to create an enchanting evening ambiance while minimizing light pollution.

Axis is uniquely adjacent to Montage Park, the sixth in a series of interconnected parks within the master plan. The landscape design incorporates wide pathways and "glass-seeded" decorative paving that forms a ribbon-like pattern, physically and visually connecting Axis to the larger Millenia urban trail system.

Steering away from traditional mass planting, Axis utilizes a "pedestrian-scale" palette. Residents are greeted by a diverse array of drought-tolerant and native species, paying homage to the agricultural history of Chula Vista while providing a welcoming, wild, yet structured feel that softens the architecture.

Sustainable infrastructure can be encountered through the projects bioswale features and selective use of permeable pavers. These elements are treated as decorative landscape features rather than hidden utilities, showcasing how stormwater management can add texture and interest to the urban fabric.

Recognizing the importance of pets in an urban lifestyle, the development includes a dedicated dog park and washing station, ensuring that the high-density environment remains functional and welcoming for pet owners.

What makes Axis at Millenia my favorite project of 2025 is the professional enjoyment I found in exploring how a curated landscape palette could help color and soften the sharp lines of the architecture. I am particularly proud of the dispersed color gardens, as they transform simple corridor terminations into moments of vibrant sensory discovery, which helps to truly define the soul of this community. The hope of residents gathering under catenary lighting at the outdoor pavilion reminds me why we prioritize placemaking; it is about creating the stage where neighbors become friendsfriends, and a sense of belonging is fostered. Ultimately, my favorite challenge was transforming the relatively mundane and small amount ofur landscape area into something unique enough to provide years of seasonal change while supporting a commitment to that larger community’s vision of an integrated urban neighborhood.

Axis at Millenia is more than a housing development; it is a successful case study in "placemaking." By prioritizing the spaces between the buildings, where residents travel and engage with their neighbors, the project creates a sense of belonging and a high-quality outdoor lifestyle that serves as a model for future high-density urban settings.

McCullough also completed two additional projects with Millenia, Pinnacle at Millenia and Genesis at Millenia. We are thrilled to continue to take part in building this community through landscape architecture and urban design.

TCC Urban Greening Plan | San Diego, CA

Benjamin Arcia, M.U.D., ASLA

Studio Design Leader

Among the diverse projects that I led during 2025, the TCC Urban Greening Plan stands out.

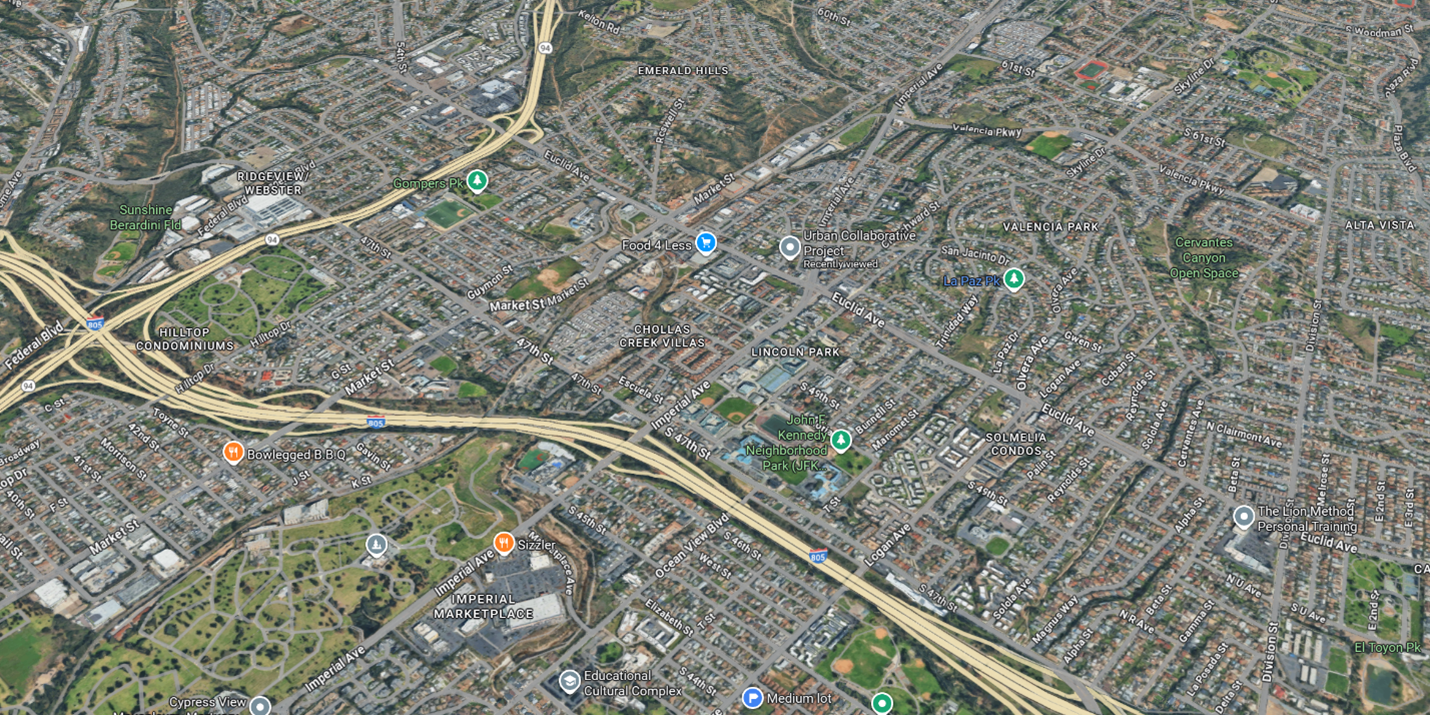

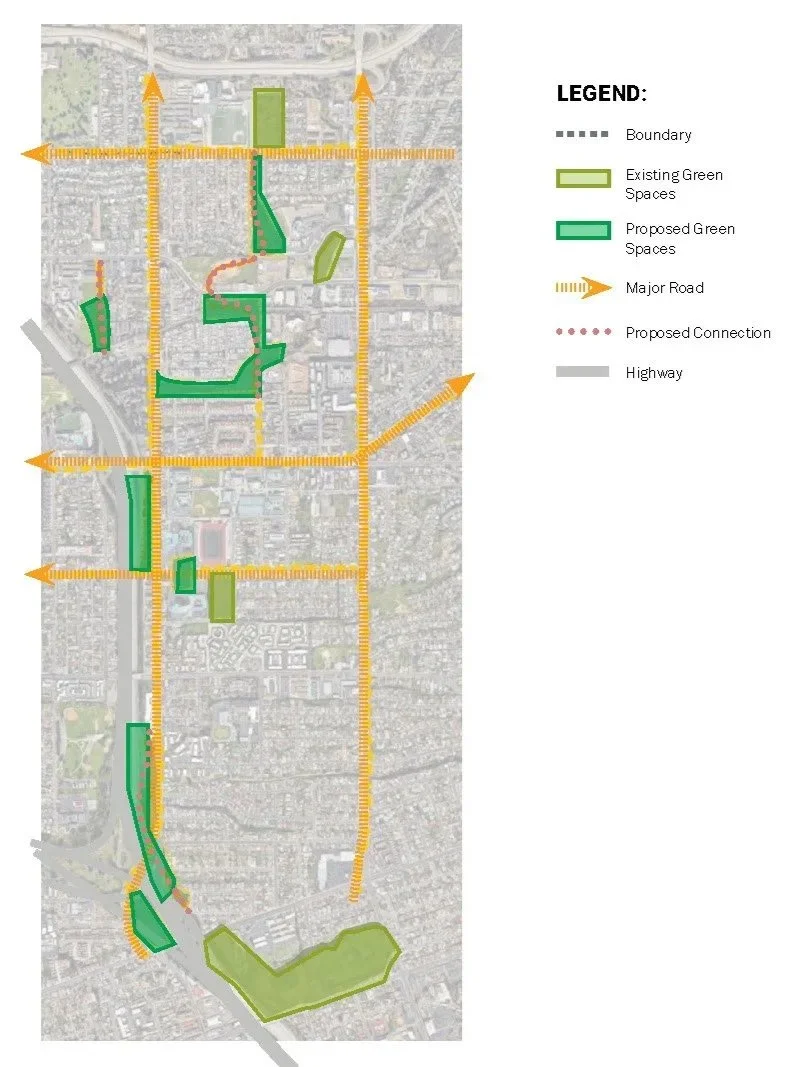

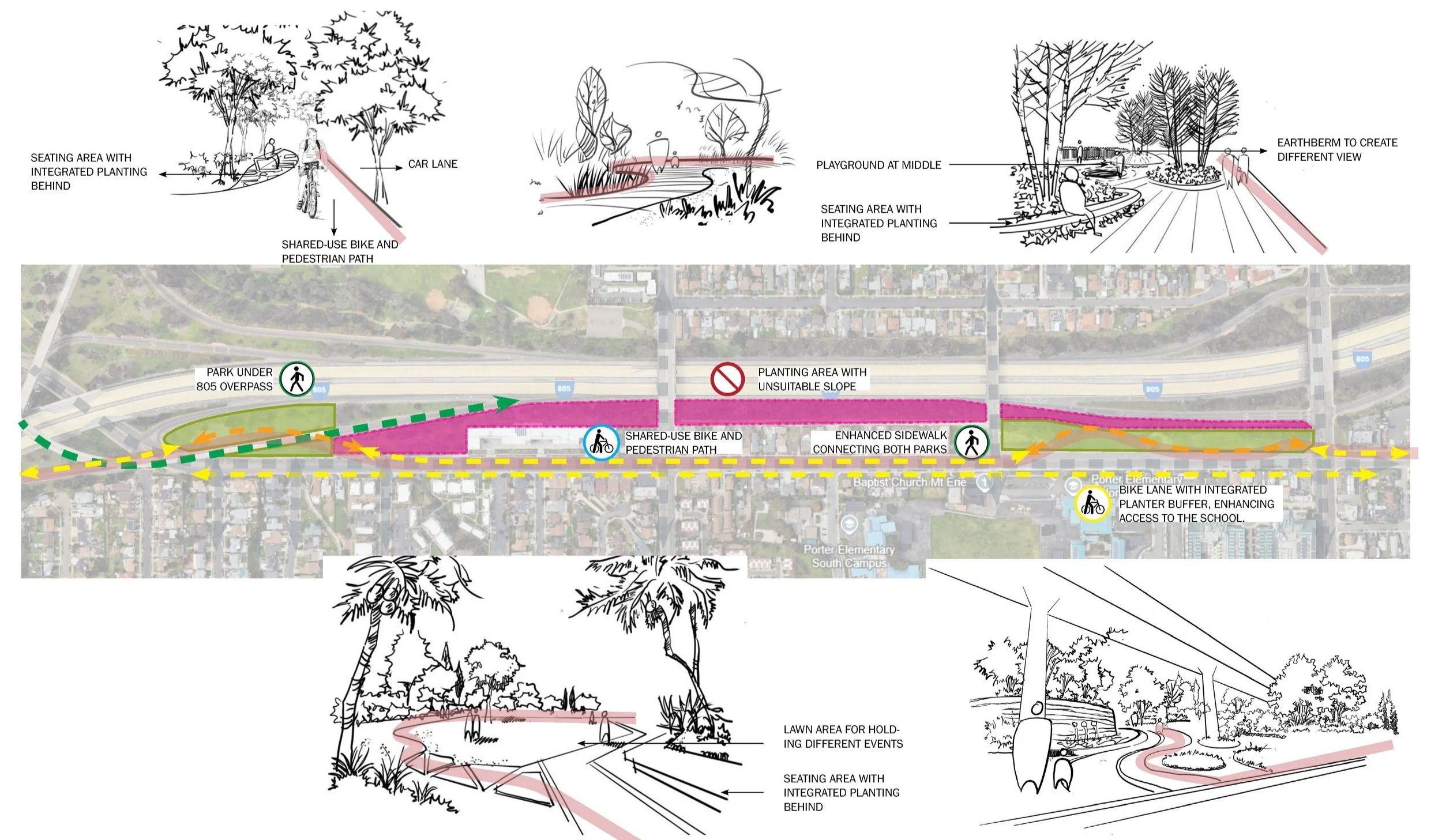

Urban Collaborative Project tasked us with envisioning a network of green spaces that could connect three neighborhoods in Southeast San Diego—Chollas View, Lincoln Park, and Emerald Hills. In Chollas View and Lincoln Park in particular, green spaces are scarce. Additionally, their street grids are fractured, plugged up by dead-ends and cul-de-sacs, forcing walkers and bikers to move along high-speed arterials (Euclid, 47th St) rather than quiet neighborhood streets.

Our mission was to identify underutilized spaces throughout these neighborhoods and figure out how to connect them so that people could enjoy a car-free, park-like setting in which to move around town.

Otis, Ben’s trusty-mate, joined him on a site visit.

Otis joins McCullough staff on a site walk of the Chollas Creek area.

We performed reconnaissance on foot and on bike. Over the course of a few weeks, our explorations started yielding an underlying scatterplot of green pockets that could connect Chollas View and Lincoln Park together from North to South. We found that instead of allowing for the creation of one contiguous linear park, the site conditions suggest that an archipelago of parks connected by bike lanes is more viable. The chief opportunities lay in the Chollas Creek floodplain and in the 805 freeway right-of-way.

Once the bones of the network were laid out, we went a step further to envision what the character of these spaces could feel like. Jiayao Tang, Junior Associate, contributed immensely to this phase of the project by creating sketches that depicted the many site-specific ideas we had compiled over months of study.

Our proposed design interventions included playgrounds, trails, sport courts, floodable parks, trailhead portals, and feature bridges. We were careful to locate loud functions like skateparks and pickleball courts near noisy freeways, and to locate quieter uses in the restored canyons.

We presented our design proposals at community meetings hosted by Urban Collaborative Project and were met with positive feedback. The concepts that we created will be used to pursue future planning grants and continue the momentum towards a more equitable public realm for these historically underserved neighborhoods.

Large projects can often be lumbering, with a lot of hurry-up-and-wait. It was refreshing to move quickly, to generate and depict our ideas in sketch form. I absolutely love the concept phase of an urban design project, and that’s why the TCC Urban Greening Plan is my choice for Best of 2025.

San Mateo County Community College District Student Housing | San Mateo, CA

Mahalakshmi “Maha” Balachandran, Int’l ASLA

Senior Associate, Northern California Office

*Images courtesy of HPI Architecture

I see the the work of a landscape designer as a tool for social equity, and the student housing project at the College of San Mateo as our most meaningful response to this calling and why it’s my choice for Best of 2025. In California, the housing crisis has forced many community college students to waver on their academic paths due to skyrocketing rents. This infill project is a transformative move by the San Mateo County Community College District to provide a residential anchor for students across its three colleges. Being a part of a collaborative design process led by HPI Architecture, we worked closely with BKF Engineers to transform a latent campus site into a residential anchor. Together, our teams navigated the technical complexities of the site to ensure this home supports academic persistence.

One of the most delicate challenges was the pivot of our initial site location. Given the deep ties to the surrounding residential neighborhoods, the team recognized that being a good neighbor was just as important as the housing itself. The district was open to proactively shifting to a new location to create a respectful buffer, ensuring we did not increase noise or visual disturbance for the longtime residents next door. This was not just a technical adjustment; it was a constructive dialogue between the campus and the community. By repositioning the density, the team managed to protect the neighborhood’s character while simultaneously creating a more secure campus feel that makes the students feel safely tucked into the heart of the college.

Our design goal was to weave essential infrastructure into a landscape that feels inherently human. How do we balance safety codes with student comfort? We chose not to let technical requirements dictate the asphalt-heavy aesthetic, instead reimagined fire lanes as expansive open lawns using reinforced turf. This fulfills emergency access needs while providing flexible green space. We opted for a living laboratory of plants specific to the San Mateo region that are both drought-resilient and deeply beautiful. As we developed the program, we also addressed a vital question: how do we accommodate both the social energy of campus life and the need for solitude? We balanced the site between vibrant, sun-drenched courtyards for interaction and shaded study nooks for quiet focus. For community college students balancing work and family, is high-quality outdoor space just a luxury? We believe it is not. It is a necessity for their mental well-being and ultimate success.

As we prepare to break ground in early spring, this project is more than just adding beds to a campus. It is a strategic effort to provide stability for students priced out of their own communities.

This project was featured on the San Mateo Daily Journal. Read more here.

Maeve | San Diego, CA

Adam Crowell, ASLA

Associate

Once again, McCullough has teamed up with Murfey Company on a new multifamily housing project in San Diego. If you’ve driven along El Cajon Boulevard recently, a popular transit corridor, you’ve probably noticed the steady wave of new development. San Diego has seen significant growth over the past decade, with new projects moving forward quickly and at scale.

Building on the success of several completed Murfey projects, the team is excited to have broken ground on one of the newest additions: Maeve. This milestone comes just a few months after the grand opening of Rainford in Mission Hills, another collaboration our team is proud of. Collaborating with Murfey Company and local architects Stephen Dalton Architects has been a rewarding and creative experience. Through open communication, strong leadership, and a shared vision, the project team has worked seamlessly together. We’re proud of the progress to date and look forward to welcoming Maeve as she comes to life. A perfect reason to choose this project as my Best of 2025.

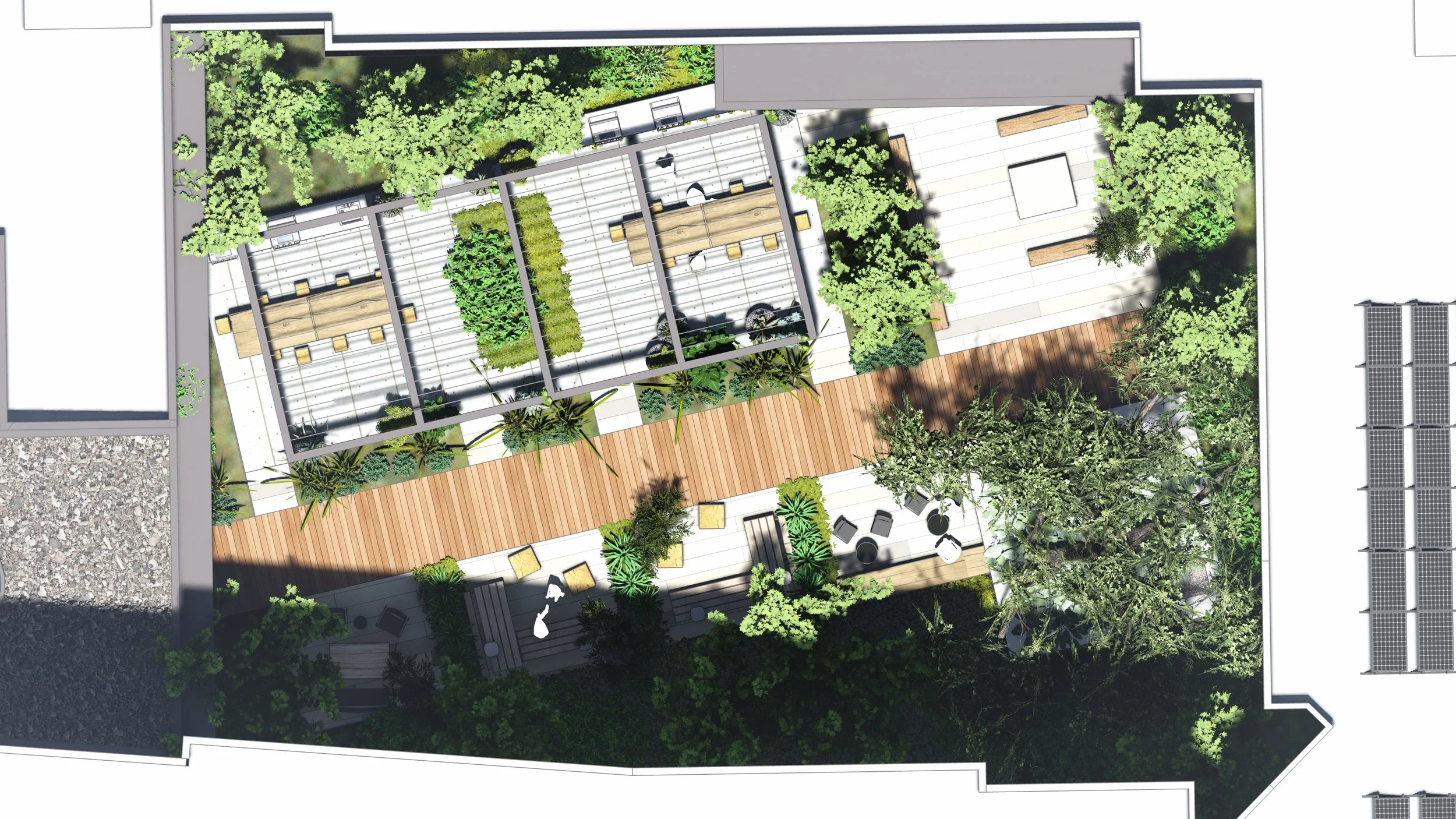

Located at the intersection of Illinois Street and El Cajon Boulevard, Maeve is a nine-level multifamily building currently under construction. While still taking shape, the project reflects an ambitious vision for urban living. Similar to past collaborations with Murfey Company, Maeve is a fully Type I construction building offering studio, one-, and two-bedroom units, activated street frontages, a central courtyard, and a rooftop amenity deck designed to support community and connection.

In alignment with the North Park Community Plan and the City of San Diego’s Complete Communities guidelines, both Illinois Street and El Cajon Boulevard will feature enhanced streetscapes. Where feasible, trees will line both sides of the sidewalk, and public amenities such as seating and bike racks will be incorporated to support pedestrian activity and neighborhood connectivity. Both the street level and the third level courtyard will feature raised planters to help with proper storm water management.

Once inside the third-level courtyard, residents are welcomed into a warm, intimate retreat designed for gathering and connection. The space invites hosting and casual socializing, with a BBQ grill and communal dining table, complemented by comfortable lounge seating oriented toward a central fire feature. Lush shade tolerant planting wraps the courtyard, softening the architecture and creating a sense of enclosure and privacy. Overhead, string lights and floating bamboo panels—suspended along steel cables—cast a gentle glow and filtered shadows, transforming the courtyard into a relaxed, enchanting setting from day into evening.

Up top is where it all comes together. Designed as an active gathering space, the rooftop amenity deck offers a little something for everyone. From cooking and connecting at the outdoor kitchen, to lounging fireside, to pulling up a chair to work or study with a view—this space was built for everyday moments and shared experiences. With views of North Park and El Cajon Boulevard, it’s a rooftop that can stay lively from sunrise to sunset.

Together, these spaces reflect a thoughtful approach to urban living—one that prioritizes connection, comfort, and a strong relationship to the surrounding neighborhood. As Maeve continues to take shape, it represents not only another successful collaboration, but a meaningful addition to the evolving fabric of North Park. The team looks forward to seeing the project come fully to life and become a place residents are proud to call home.

ZIZHU INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE CENTER + HOTEL AND RESIDENCES | SHanghai, China

Tianchi Zhang, MLA, ASLA

Associate

A CONTEMPORARY PUBLIC REALM ROOTED IN CULTURAL CONTINUITY

As the fifth phase of our original Zizhu Purple Bay Master Plan started several years ago, the Zizhu International Conference Center + Hotel and Residences was an opportunity to shape a unified landscape that supports global events while remaining deeply connected to local tradition and human-scale experience. Located in a fast-growing area of Shanghai, the project asked the landscape to handle ceremony and scale for international conferences, provide comfort and daily use for hotel guests and residents, and tie together a complex mix of programs into one cohesive place.

Rather than treating the conference center, hotel, and residential towers as separate entities, the landscape establishes a continuous ground plane that unifies the development. Each program is shaped by its functional needs, yet all are connected through a shared material palette and a contemporary interpretation of classical Chinese garden principles, such as balance, procession, framed views, and layered experiences.

At the conference center, the landscape takes on a formal and civic character. The grand plaza is designed as a clear and flexible forecourt that can host large international events while remaining accessible for everyday use. Structured paving, raised planters, and accent trees define circulation and arrival, while shared surface strategies allow the space to accommodate both pedestrians and VIP access when needed.

Moving toward the hotel and residential areas, the landscape becomes softer and more intimate. A planted hotel arrival garden with a central water feature creates a welcoming first impression, while shaded paths and layered planting lead residents to a sunken courtyard designed as a quiet retreat. Above, the Conference Center Sky Garden offers an elevated courtyard experience anchored by specimen trees and a circular opening that brings daylight and symbolism into the space.

A carefully selected planting palette including ginkgo, camphor, cherry blossom, and osmanthus reinforces seasonal change, cultural meaning, and sensory experience throughout the site, allowing the landscape to evolve naturally over time while remaining deeply rooted in place.

This project stands out to me as a Best of 2025 for its ability to bridge past and future, ceremony and daily life. As the project manager, I enjoyed working closely with our design principal, David McCullough, to develop the overall landscape concept from early planning through design development. Through close coordination with Gafcon, Gensler, and the Zizhu design team, we pushed the design forward by introducing new ideas, testing spatial strategies, and then refining the landscape based on detailed and thoughtful feedback from all parties. This back-and-forth collaboration was essential to shaping a landscape that was both ambitious and grounded in the client’s vision.

The Headquarters at Seaport | San Diego, CA

Kira Becker, ASLA

Associate, Los Angeles Office

Every once in a while, you come face to face with a site that seems to have been patiently waiting for new sense of life. The Headquarters at Seaport is one of those rare encounters. Anchored at the edge of San Diego’s Seaport Village, the historic Spanish Revival style building is bursting at the seams with character, history, and unrealized potential.

The 1939 building was designed by local architects Charles and Edward Quayle as a bold civic experiment - a single centralized location for the San Diego Police Department that housed courtrooms, an emergency hospital, administrative offices, and even a jail. Its architectural language was unmistakably of its time - Spanish Revival had been popularized by the 1915 Panama-California Exposition in Balboa Park and by the 1930’s it was San Diego’s prevailing civic style.

When the police department relocated in 1987, the building sat vacant for years. It became the subject of a prolonged debate on whether it should be adapted, reimagined, or erased all together. Thankfully, preservation efforts prevailed and the site was ultimately designated a historic landmark. In 2013, it reopened as The Headquarters at Seaport Village and took on a new life as a retail and dining destination.

One of the most defining features of the building is its 68-foot-tall watchtower, which serves as a dramatic entry into the central courtyard. Visitors pass through the tower and emerge into an enclosed interior space surrounded by shops and restaurants. While the architecture remains beautiful and the location is as good as it gets, much of the site feels under-realized. Key edges, particularly the front promenade, lack the activity and sense of arrival the building deserves, and the site’s potential as a social and cultural heart remains largely untapped.

Our work begins with a simple but delicate question: how do you reawaken a historic place without overwhelming it? We believe the answer lies in a mix of restraint, resonance, and activation. Given the building’s proximity to Seaport Village, strengthening the physical and experiential connection between the two is central to the design. We are reimagining the front promenade along Harbor Drive as a grand entrance that can flex as a marketplace or gathering space that invites activity and discovery.

The design looks holistically at all four sides of the building, working to engage each edge and draw energy inward. Within the courtyard itself, we are considering how programming, tenant mix, and flexible use can transform the space into an active destination throughout the day and into the evening.

Subtle material and landscape interventions work hand in hand with this activation. We are working with local artisans and artists to source authentic woven and wrought-iron furniture and lighting and decorative terracotta pots. The addition of Spanish-inspired plant material and carefully balanced moments of art and color layer warmth and texture into the space. Our team is also rethinking lighting strategies to extend the life and energy of the site into the night. In parallel, we are thinking critically about the types of tenants that can fill vacant spaces that compliment one another and support a lively, social environment.

It’s not difficult to imagine why The Headquarters quickly rose to the top of my most meaningful projects of 2025. This project presented a unique opportunity to bring new life to a historic site while respecting and working within the beauty that already exists. Equally important was our collaboration with the team at LBX Investments, whose collaborative and creative approach has made this project especially rewarding. Together, we look toward a vibrant future for The Headquarters that embodies San Diego’s distinct character and spirit.

White Sands | La Jolla, CA

Sophia Rumpf, ASLA

Associate

2025 brought in many new and exciting projects, but one in particular has reinvigorated me, serving as a humbling reminder of why I joined this profession. I am genuinely excited and honored to be working with Humangood, a nonprofit organization dedicated to serving the elderly community, on the redesign and renewal of the outdoor community spaces at White Sands La Jolla. From our very first conversations with the Buildings and Grounds Committee and its director Lorraine, it was clear that we share a common ethos: a belief in integrating people with nature to enrich daily life, strengthen community, and support health and well-being at every stage of life. That mission aligns with our values at McCullough, where we believe outdoor environments are so much more than just scenery; they have the power to enrich people’s lives. We strive to curate them with care.

Positioned directly on the La Jolla coastline, White Sands La Jolla is a Life Plan Community where residents live immersed in one of Southern California’s most remarkable natural settings. The ocean is not just a backdrop here, it is part of daily life, shaping routines and lifestyle, resulting in a coveted sense of place. Humangood has worked hard to deliver a balance of independence, care, and continuity at White Sands, offering residents the unique opportunity to age in place in an environment that fosters connection to the coast, and one another. To be entrusted with a site of such extraordinary beauty and importance to its residents is a privilege and a responsibility we take seriously.

Our design process begins with listening, and in this case particularly to the priorities of residents. Humangood puts its resident-first mission into action by involving them directly with the design process. The Building and Grounds Committee at White Sands holds monthly meetings where participants share ideas and feedback, empowering them to shape the environment they call home. We have and will continue to attend these meetings periodically, ensuring that their needs, preferences, and lived experiences inform every decision.

A major focus of our work will be strengthening the physical and visual connection to the beach below. We see opportunity to enhance and expand usable oceanfront land, allowing residents to enjoy activities while viewing and interacting with the ocean. Though we may face development challenges on these highly protected coastal lands, we hope to find ways to improve beach access, as residents are concerned for any obstacle that could impede their enjoyment of the beach.

Accessibility, comfort, and safety will be guiding principles throughout as well. Keeping in mind the age and physical limitations of current and future residents, we will make design decisions that ensure that outdoor areas are comfortable and intuitive to use. Thoughtful circulation, appropriate shading and lighting, and clear organization of space will help improve residents’ confidence, security, and comfort as they move through the grounds. Durability is equally important; materials and detailing must stand up to wind, salt air, and weather while remaining beautiful and maintainable over time.

White Sands is an undeniably special place that has evolved over the years. We at McCullough are deeply honored to contribute to its next chapter. The outdoor spaces at White Sands are not just amenities, they are extensions of residents’ homes and vital settings for community life. Whether gathering, exercising, reading, or simply enjoying the view, residents deserve environments that feel purposeful, protected, and inspiring. Our goal is to help create outdoor spaces that support connection, vitality, and joy, leaving a lasting mark on a community that already embodies the best of coastal living.

C Street VIsioning | San Diego, CA

Jiayao Tang, ASLA

Junior Associate

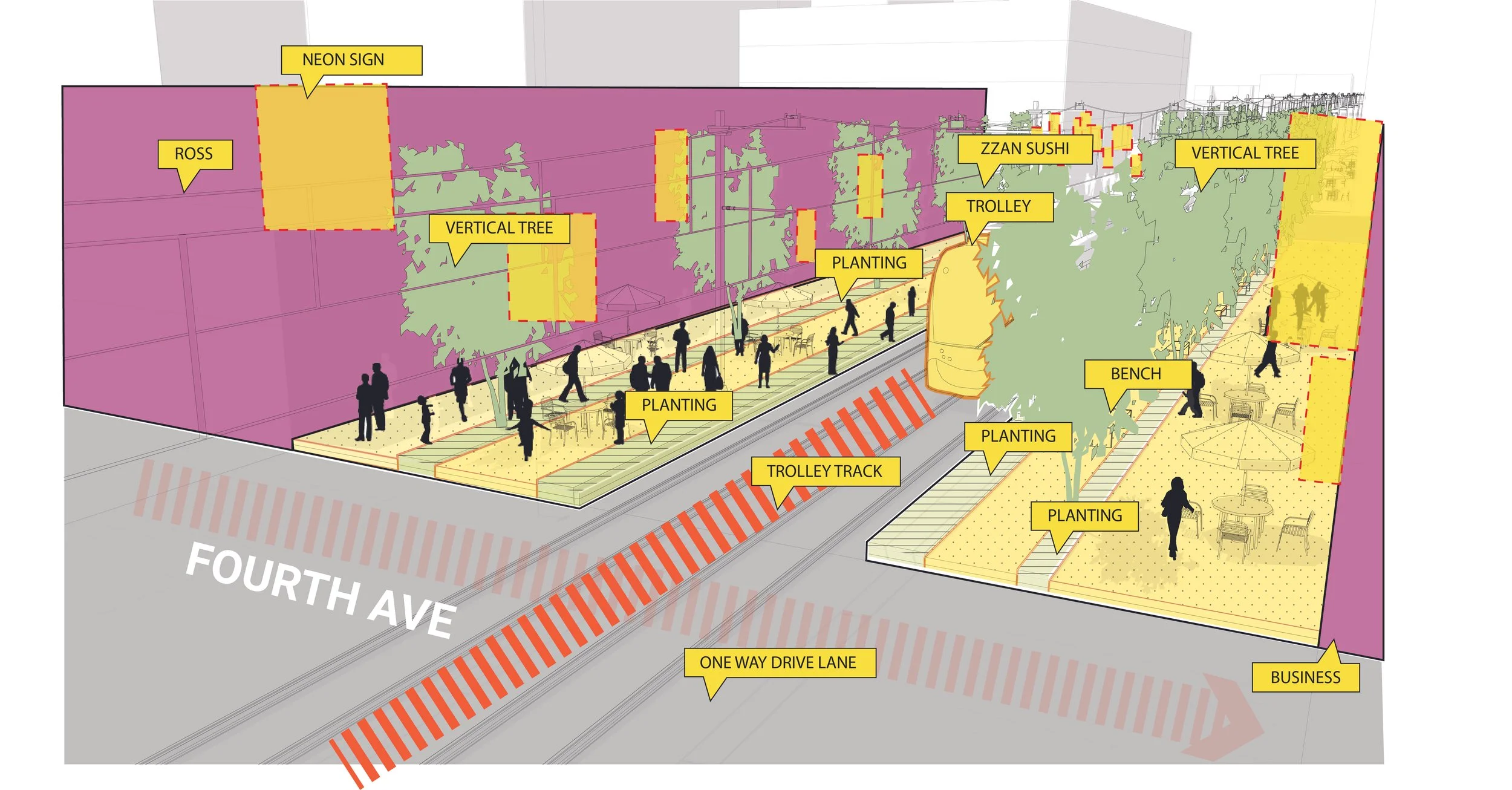

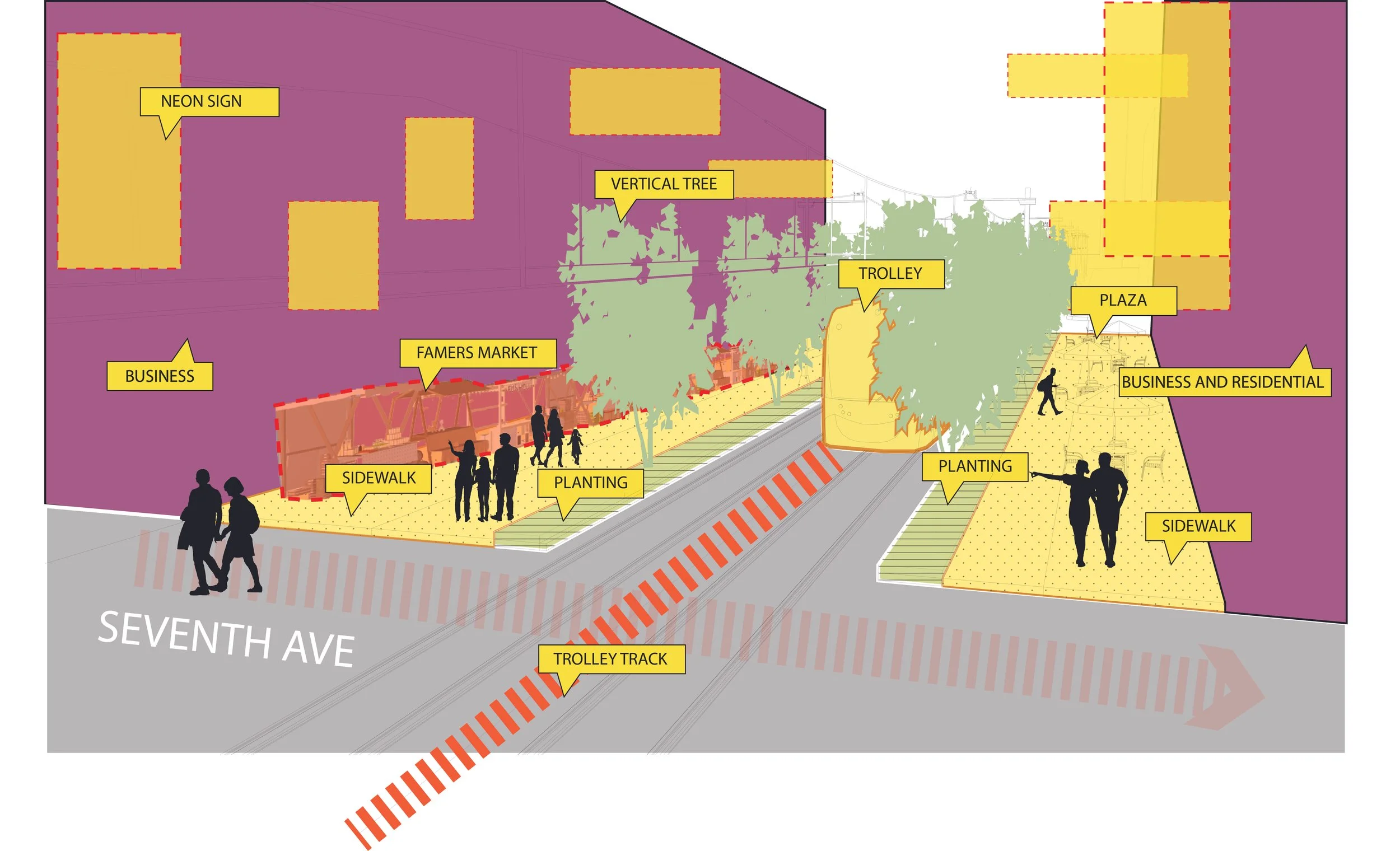

I selected C Street as a Best of 2025 because I’m happy to contribute to a project that transforms a transit-oriented downtown corridor into a vibrant cultural street that invites people to gather, linger, and engage with the city.

Project Scope

The C Street project reimagines a historic downtown corridor in San Diego as a people-centered cultural street. While the corridor serves as a key trolley route, it had long functioned primarily as a transit and pass-through space rather than a destination. Our goal was to transform C Street into an active public realm—one that attracts people, supports local businesses, and celebrates cultural identity.

Through strategic streetscape redesign, cultural programming, and placemaking interventions, the project seeks to bring new energy to the street by encouraging people to gather, linger, and engage with their surroundings.

Design Challenges and Approach

The primary challenge was balancing multiple modes—trolley operations, vehicular access, and pedestrian activity—within a constrained right-of-way, while creating a welcoming and memorable street experience. In response, the design prioritizes pedestrian comfort and visibility through expanded sidewalks, seating zones, and planting buffers, while maintaining clear and safe trolley circulation.

Another key challenge was establishing a strong identity for the street. Rather than relying solely on hardscape or planting improvements, the design integrates cultural elements—public art, neon signage, and flexible community spaces—to create a sense of place that resonates with both locals and visitors.

Unique Features and Outcomes

Cultural Expression and Identity

Playful cultural icons, including large-scale art elements such as the climbing panda, introduce moments of surprise and character, making the street visually distinctive and memorable.Neon Signage and Nighttime Activation

Inspired by historic entertainment corridors and night markets, neon signage activates building façades and extends street life into the evening, supporting local businesses and enhancing safety through increased visibility.Flexible Community Spaces

Designated farmers market and event zones transform portions of the sidewalk into adaptable platforms for vendors, performances, and seasonal programming.Greening and Comfort

Continuous planting areas and vertical trees provide shade, soften the urban edge, and improve the overall pedestrian experience, reinforcing the street as a place to stay rather than pass through.

Design Charrette

As part of a collaboration between McCullough, SmithGroup, The City of San Diego, and the Downtown San Diego Partnership, along with several other notable community and design professionals, a walking tour and design charrette occurred in late October 2025 at the SmithGroup’s downtown San Diego office at Five50West to engage progressive thinkers in our built environment on how to plan strategically for the corridor. Many ideas were shared and incorporated into the formation of a website where ideas can continue to evolve and become solutions. A lively visioning process and proposed strategies for the C Street Corridor transpired in the discussion, aiming to transform it into a vibrant, multi-functional urban space. We all agreed, activation is key to the long-term success of a street.

Impact and Value

The C Street project demonstrates how cultural placemaking and thoughtful streetscape design can transform an underutilized corridor into a vibrant civic destination. By prioritizing people, culture, and community life, the project shifts the perception of C Street from a transit corridor to an active urban experience.

This project reflects our belief that streets are more than infrastructure—they are social spaces that connect people, culture, and city life. C Street stands as a model for how urban streets can be reactivated to support economic vitality, cultural expression, and everyday community engagement.

Hidden Oak | San Diego, CA

Adis Tutusic, Int’l ASLA

Junior Associate

Hidden Oak stands out as one of the most meaningful and challenging projects of 2025; not because of its scale, but because of the care taken to thoughtfully integrate architecture and landscape within one of Southern California’s most sensitive natural settings. Located east of Old Coach Road, north of downtown San Diego, the project by Shea Homes, introduces contemporary farmhouse homes gently tucked into the hidden folds of California’s native landscape, surrounded by preserved biological resources and protected wetland systems.

From the beginning, Hidden Oak represented a rare and meaningful opportunity for a landscape architect to collaborate on a project that bridges generations of planning, regulation, and holistic design intent. Strict requirements from the local jurisdiction, fire department, and slope stability regulations demanded that grading, access, fire safety, and habitat protection work together as a single system. Rather than treating these constraints as obstacles, the design embraced them as guiding principles, restoring disturbed areas to functioning natural landscapes while establishing new biological zones that strengthen existing habitat conditions.

A key goal was to return the land to nature while allowing carefully placed development to coexist respectfully within it. Sensitive wetland areas were protected and enhanced. Slopes were stabilized with naturalistic landforms, and planting strategies were designed to reinforce ecological integrity. Streets and circulation were intentionally kept visually subdued, allowing the landscape to remain the dominant experience and reinforcing the feeling of the site as one unified natural environment rather than a conventional subdivision.

The architectural and landscape language is rooted in the character of Southern California: contemporary farmhouse forms paired with timeless materials such as stone, native oaks, and steel. These elements create a refined yet grounded identity; modern but deeply connected to the land’s agricultural and ecological history. The result is a community that feels discovered rather than imposed, where homes emerge naturally from the terrain and the surrounding landscape tells a story of stewardship and restraint.

Hidden Oak represents a successful balance between development and preservation. It demonstrates how thoughtful design, regulatory collaboration, and respect for place can transform a highly constrained site into a cohesive, resilient, and enduring community. For these reasons, it stands as my pick for one of the most inspiring projects of 2025.

San Diego Community College District STUDENT HOUSING | SAN Diego, CA

Olivia Wax, ASLA

Junior Associate

Some projects stick with you because they’re flashy. Others because they’re meaningful. This one earns its spot for being both quietly complex and deeply impactful. Urban, educational, and rooted in doing more with less.

Located in the heart of downtown San Diego at 17th and B Streets, the San Diego Community College District’s first student housing project, in collaboration with The Michaels Organization and TCA Architects, reimagines two interior courtyards and the surrounding street frontage as functional, resilient outdoor spaces that support student life while responding to real site constraints. The goal was simple on paper: create welcoming, attractive outdoor environments. The reality? A tight urban site, mature trees, drainage challenges, and heavy shade, all asking for thoughtful, intentional design.

My primary role focused on the planting design, and a detailed site visit to measure and assess existing trees. Understanding what was already working and what absolutely had to stay was critical to shaping the design. Both courtyards are heavily shaded, which immediately narrowed plant options, while the presence of bioretention basins and infiltration challenges required an added layer of coordination. Because infiltration was limited, all planters were designed to be lined, allowing us to control soil conditions and protect surrounding infrastructure. The resulting plant palette emphasizes California native and climate-adapted species that look good year-round. The selection balances low to moderate water use, durability, and texture, providing visual interest without demanding constant maintenance.

At the street frontage, planting was carefully designed to maintain visibility from the sidewalk while subtly enhancing safety. The landscape visually connects the campus to the surrounding neighborhood, softening the edge without creating hiding places, an underrated but critical win in an urban educational setting.

The biggest challenge was designing lush, healthy planting in a space that doesn’t naturally support it. Between limited sunlight, constrained soil volumes, and drainage limitations, every plant choice had to earn its place. The solution was equal parts site observation, restraint, and strategy. Selecting shade-tolerant natives that thrive in controlled soil conditions. Using lined planters to manage water and protect tree roots. Designing plant layers that feel full without overcrowding. Sometimes the smartest move isn’t adding more, it’s choosing better.

What makes this project memorable isn’t a single design gesture, it’s how many competing priorities it successfully balances. It supports student use, respects existing trees, addresses safety concerns, and still feels calm and inviting. I’m especially excited to see how the courtyards are used once fully activated, spaces like these often become the unofficial living rooms of a campus. If students choose to study, gather, or just breathe here between classes, that’s a design success.

I chose this project for “Best of 2025” because it reflects the kind of work I want to keep doing: thoughtful, context-driven landscape architecture that quietly improves daily life. Sometimes it’s not about making a loud statement, it’s about making space better for the people who rely on it every day. Urban education projects come with real constraints, but they also offer real opportunities to make an impact. This one did exactly that.

La Quinta Cultural Campus | La Quinta, CA

William Glockner, MLA, ASLA

Junior Associate

As we enter the new year of 2026, it is time to pause and reflect on the work of the past year and consider which efforts represent bold steps forward for our firm. In reviewing what we have accomplished, a distinct realization occurs. The year of 2025 marks our firm’s first year of designing and working alongside AI tools. When considering how AI will alter the world, we like to consider the introduction of computers.

When computers were first invented, there was a widespread panic that they would take over all industries and humans would either: become destitute OR usher in a golden age, replete with flying skateboards. Alas, our flying skateboards are yet to be. However, whether we are living in a golden age or on the brink of destruction remains an open question. As ever, mankind continues to teeter between excellence and desolation.

As a firm, we have chosen to nudge that balance toward excellence.

Our team leaned into AI as a tool to become more efficient, more creative, and more ambitious on behalf of our partners. No project better demonstrates the potential of AI to streamline the design process while enhancing creativity than our work at La Quinta. At the start of the year, the La Quinta project was already an impressive concept: a 300-foot-long, 10-foot-wide snake-shaped path paired with a Cahuilla basket pattern across the ground plane.

As the year progressed, our team began designing with AI, allowing us to push beyond the initial concept and further refine this sprawling monument through a series of engraved concrete tiles that retell iconic Cahuilla legends.

Working alongside a tribal consultant, our team began sketching a series of plants and figures relevant to Cahuilla culture, then translating these into concept renders using Photoshop. We quickly ran into challenges: establishing a consistent art style and affordably executing more than 40 custom concrete murals, each averaging six feet wide.

Safe to say, our eyes were bigger than our pencils.

What changed was the realization that by feeding our base sketches into AI tools, we could refine the art style and visual direction far more quickly. This allowed us to iterate rapidly, steer the work with intention, and ultimately arrive at a cohesive aesthetic. All this while maintaining reasonable budget expectations and meeting our client’s timeline. Once the designs were approved, a new question emerged: how do we turn beautiful images into carvable surfaces? The answer was to vectorize the artwork, refine the linework, and convert the images into black-and-white, CAD-compatible drawings.

Through close coordination with our subcontractors, we developed a clearer understanding of viable line weights and color contrasts that could be achieved in concrete without compromising legibility or structural integrity. As with any project, contractor coordination was essential. Our discipline is not art for art’s sake; our work must be safe to walk on, durable, and capable of supporting repeated loads. With the finished product delivered on time, and exceeding expectations, we were given the opportunity to expand the scope further.

To us, the logical next step was to build on the 40 art pieces by creating an accompanying audio tour that explores the Cahuilla lore and culture that inspired them, accessible via QR codes at the La Quinta Cultural Center.

With client approval, our team fully entered storytelling mode. Working closely with tribal consultants, we co-wrote more than 40 narrative vignettes rooted in Cahuilla tradition and culture. AI tools assisted in editing, refining, and tightening each story, allowing a small team of writers to produce high-quality, concise, and distinct narratives for every tile. Beyond that, we were able to weave these individual stories into a larger arc that underscores the historic migratory patterns of the Cahuilla people.

The La Quinta project illustrates how AI, when used responsibly, allows a small team of designers to operate with the reach of sculptors, writers, graphic designers, and historians. This ability to execute more work in less time, at a high level, enables us to pursue more ambitious and contextually relevant ideas. While the future of our profession may not include worrying about flying skateboards, it will demand that our ability to select an appropriate planting palette be matched by our understanding of the cultural context of a place.

Our role is shifting from the mechanics of design toward the spirit behind it. Rather than being consumed by the placement of paths, plants, and pipes, we are increasingly focused on what a place is saying… and what it has the potential to say.

In the years ahead, our need to excel at CAD, code, and calculations may decrease in importance. But our ability to understand and articulate the relationship between people and place will continue to define the profession. Though little in this world is certain, the creative future will likely resemble its past: a persistent pursuit of our wildest dreams, mediated by our wildest machines.